Please join the SNCC Digital Gateway Project for a conversation with five veterans of the Civil Rights Movement in Georgia. In 1961, field secretaries from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating... Read More

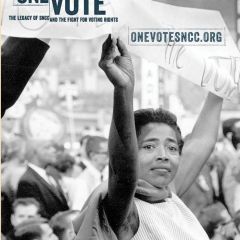

One Person, One Vote

2014 to 2016

Emerging Networks

In a pilot initiative that is part of a longer-term collaboration, Duke University and the SNCC Legacy Project plan to chronicle the historic struggles for voting rights that youth, converging with older community leaders, fought for and won.

In our history, the central role of students in the voting rights struggle has largely been omitted. There has been a tendency to emphasize the role of nationally known, charismatic leaders, ignoring the local leaders and foot soldiers who make change possible. Too many people in our academic culture have emphasized a top-down perspective. As a result, many SNCC veterans have concluded that academic historians are not interested in their analytical contributions, oral histories, or historical papers. This must change if we are to get the thinking of grassroots activists into the record.

Historical context is essential to understanding this important project. After the Civil War, the central question facing America was how to define equality between the races. Some urged dividing up plantations among former slaves—forty acres and a mule—but except in a few isolated areas, that never happened. Economic equality disappeared as an item of contention. With the 14th and 15th Amendments, some political reforms occurred. Black men were given the right to vote, and a series of bi-racial Reconstruction governments came into being, enacting laws providing for public education, publicly built roads, and some social services. But resistance from conservative whites and the Ku Klux Klan persisted. Then in 1877, the Republican party sold out the black South to procure electoral votes for Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican presidential candidate. Federal troops were withdrawn. Reconstruction and bi-racial governments were over. Black men could still vote in some elections but only on the condition that they not challenge the primacy of former Confederates.

Then in the late 1880s and 1890s, the Populist revolution occurred. Poor white farmers—soon joined by poor black farmers—started coalition movements to unseat the rich Bourbon Democrats in charge of Southern states. In many states the Populist coalitions exhibited great strength, including in North Carolina, where the bi-racial “Fusion” movement took control from 1894-1898. To fight back, powerful white people raised the flag of racial solidarity. They portrayed black men as determined to rape white women, urged violent repression of black politicians, and held a series of “reform” Constitutional conventions that took the vote away from blacks in every Southern state. By 1901, the “Jim Crow” system of segregation had taken hold across the South. Now there was not only no chance for equal economic opportunity.

It remained that way until World War II. Seizing the argument that Americans were fighting a war against racism in Europe and for political freedom everywhere, black Americans adopted the “Double V” slogan—victory at home as well as abroad. The NAACP grew from 50,000 members to 500,000 in four years. Ella Baker, the Virginia-born NAACP director of branches, organized protest groups in every Southern state. Civil rights for black Americans was back on the national agenda. In 1954, the Brown decision outlawed segregation in schools. That was followed in 1955 by the Montgomery bus boycott, a collective demand for equal access to public transportation led by Rosa Parks and others.

But it was only with the emerging civil rights revolution in the 1960s that voting rights once more took center stage. In 1960, a group of young people unexpectedly seized center stage in what became a pivotal political shift. Led by student veterans of the sit-in movement, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was formed at Shaw College during Easter weekend at a meeting suggested by Ella Baker. From that point forward, SNCC became the cutting edge of the direct-action civil rights movement, focusing on both political freedom and equal economic opportunity. Its full-time student workers—“field secretaries” working with local black activists to generate grassroots activism and encourage new community organizations across the Deep South—was key to getting the Voting Rights Act passed. The Act was one of the most significant pieces of legislation of the 20th century.

The parnership of the SNCC Legacy Project and Duke will encourage young people today to consider the lessons of the past and look to these examples of courage and intelligence, as well as strategies of organizing that helped them achieve their objectives.

The potentially rich synergies for this work were evident when six SNCC veterans (Charlie Cobb, Courtland Cox, Ivanhoe Donaldson, Bruce Hartford, Jennifer Lawson, and Judy Richardson) visited Duke in November 2013. One of their priorities while on campus was to talk with students about their concerns, passions, and worldly engagements. In two lengthy sessions, one at the Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture and the other at the Forum for Scholars and Publics, the SNCC activists met with Duke community members, including 20 undergraduates, to explore the potential for their involvement with Duke’s present-day social and political action. These interactions laid the foundation for active student participation in the project moving forward.

In response to these events and the energy they generated, the SNCC Legacy Project, Duke’s Center for Documentary Studies, and the Duke Libraries have embarked on a pilot project to use primary and secondary sources to write, teach, and explore the history of the youth-led, grassroots campaign for voting rights between 1960 and the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. A network of SNCC activists, scholars, students, archivists, web designers, and curriculum experts will be assembled for the task.

At the core of the project, SNCC organizers—those who organized much of the grassroots struggle for voting rights in the 1960s, in their teens and 20s—will return to campus in 2014-2015 as activists-in-residence. They will work collaboratively with undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, archivists, and others to engage with SNCC’s documentary legacy and to explain the materials to those who want to use them. The SNCC organizers have been adamant that working with current students is key to the work they plan to do on campus.

With the help of Humanities Writ Large, the project will employ a group of undergraduate research assistants and a graduate student coordinator. These students will join the SNCC activists-in-residence in a workshop setting to research and interpret primary materials and shape content for a new documentary website

People

|

SNCC Veteran President, SNCC Legacy Project |

Director, John Hope Franklin Research Center |

Director, Center for Documentary Studies |

|

SNCC Veteran Senior Vice President for Television and Digital Video Content at the Corporation for Public Broadcasting |

Director, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library |

Senior Research Scholar, Center for Documentary Studies |

Highlights

|

Voting Rights, Then and Now: The SNCC Legacy Project

-- Sep 24 2015

An ongoing partnership between Duke's Center for Documentary Studies, Duke University Libraries, and the SNCC Legacy Project was the subject of... Read More |

The SNCC Digital Gateway is Online

-- Jan 3 2017

Announcing the new documentary website SNCC Digital Gateway: Learn from the Past, Organize for the Future, Make Democracy Work. It is the product of... Read More |

Events

|

Strong People: SNCC and the Southwest Georgia Movement -- Feb 4 2017 - 5:00pm to 6:30pm |