Listening to the Silence of War

by Sharon Raynor

I'm Sharon Raynor, one of the Humanities Writ Large initiative's three Visiting Faculty Fellows this spring. Since 1999, I have been documenting the lives of Vietnam veterans in rural areas of eastern North Carolina, from Raleigh/Durham through Goldsboro, Greenville, Wilson and Clinton. Their narratives are an integral part of "Breaking the Silence: The Unspoken Brotherhood of Vietnam Veterans," an oral history project initially funded by the North Carolina Humanities Council. It includes interviews, documentary photography, site-specific installations, and academic papers and conferences. There have also been community forums and presentations where the veterans have been able to tell their own stories. They are products of the same rural Carolina milieu, with a shared experience of its racial divide, and together they endured war and trauma. They have much in common.

"There is a void...an absence...a silence. There were no voices. There were no structures of feeling or support. So I went in search of voices-in search of community."

- Charlotte Pierce-Baker, Surviving the Silence

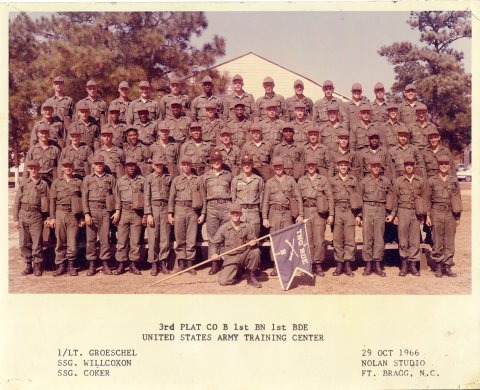

"Breaking the Silence" reveals the experiences of men who fought in Vietnam and lived to return to the same small, rural communities they had left, though they came back as very different men. They tell of being drafted or enlisting for service, of leaving homes and segregated communities for integrated battalions, of fighting for civil liberties, freedoms and racial justice abroad while the Civil Rights Movement was proceeding at home. They tell of violent loss and disappointing homecomings followed by decades of silence, of personal re-adjustments and survival. Most of the participants have been African American, but either way they were among the first to serve in fully integrated troop battalions in a combat zone, so their stories have special significance.

This project has been ongoing for thirteen years because it tapped a community that was also in search of something, a lost brotherhood that had been left behind in Vietnam. Most of the veterans participating today have been involved since the beginning. The success of the project is measured not only by the stories recorded but even more by improvements in the quality of life of these veterans and their families. They are forever united by the silence of war...

"What I want for my daughter, she shall never have: A world without war, a life untouched by the bigotry and hate, a mind free to carry a thought up to the light of pure possibility."

- W.D. Ehrhart, From "Why I Don't Mind"

Perhaps my work with Vietnam Veterans was predestined. The last American troops withdrew from Vietnam on March 29, 1973; I was born the very next day (which is now the official "Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans Day"). As the daughter of a Vietnam veteran, I was constantly seeking answers to questions about the war and the profound silence that ensued and engulfed our family. This oral history project emerged from my personal journey. I learned from my father that a child should always be willing to listen even if nothing is being said. Silence can be very profound; even silence has its own story to tell.

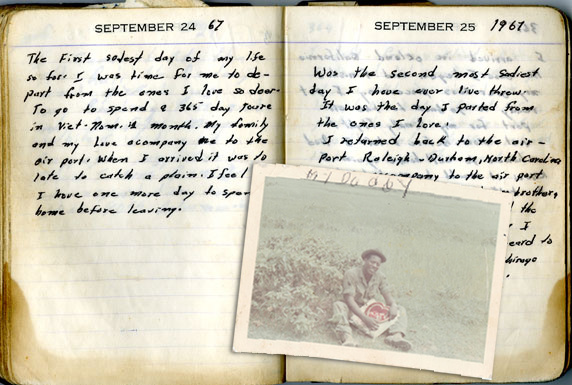

My father's silence was illustrated by his diary and by photographs that he brought home from the war. Hidden away from prying eyes, these documents only told part of my father's story, so I went in search of the rest. I was intrigued about how this culture of Vietnam veterans somehow provided comfort for my father that he couldn't get from his family or from me, his own daughter. Then, just two years after the project started, while waiting through my father's silence, I experienced a personal trauma of my own and was diagnosed with PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). I did not completely understand what it meant for a combat veteran to live with PTSD until I experienced my own trauma. We had all become mirror images of the other as we tried to reconcile our fragmented lives.

While journeying through my own silence, I continued to encourage the veterans to break theirs. When I could not find the words to tell my own story, I could better hear their voices. As the oral history progressed and the narratives continued to grow and develop, I found answers to my questions about war and silence. While I learned to listen to the silences of their stories, I also learned how to hear the story that my own silence tells.

"War reduces everything to silence. Every soldier's grave a place too loud for sleep."

- E. Ethelbert Miller, "First Poem"

And now my own story has brought me to Duke University as a Humanities Writ Large Faculty Fellow. I arrived on a rainy January day, but the welcome has been warm from the moment Floyd Borden, the History Department Business Manager, showed me to my office space. Historians Bill Chafe, Ray Gavins and Adrian Lentz-Smith shared coffee and conversation, Lee Baker and Chandra Guinn offered generous advice and a welcoming smile. At the Center for Documentary Studies, I was immediately invited into a faculty meeting by Charlie Thompson. The center's director, Tom Rankin, and faculty members Michelle Lanier, Barbara Lau and Duncan Murrell spoke with me about the fascinating work taking place there and about the enticing prospect of a Veterans Project at Duke.

I knew that I had found a wonderful home for my scholarship and a fine place for the veterans to visit and be heard. More on that next time.

"He who is a friend, is a friend always, and brothers are born for adversity."

- Proverbs 17:7

"Words have weight - you bear with me the weight of my words, suffering whatever pain this burden causes you - in silence. I bow to you."

- bell hooks, Remembered Rapture

Referenced People

|

Associate Professor of English, Director of the Graduate Education Program

|